Papua New Guinea Language Diversity: 800+ Varieties

Papua New Guinea – The World’s Most Linguistically Diverse Nation

Did you know that Papua New Guinea is the most linguistically diverse country on Earth? This island nation, located in the heart of Melanesia with just around 10 million people, speaks over 800 different languages — that’s nearly 12% of all the world’s languages! Every valley, mountain, and island seems to have its own unique way of speaking, showing the extraordinary linguistic diversity in PNG.

How did so many Papua New Guinea languages emerge in one place? Now, with us, uncover the origins of this incredible diversity, explore the main language groups, and see how Tok Pisin became the bridge connecting people across the nation.

Why So Many Languages? Geographic and Historical Factors

Papua New Guinea’s remarkable linguistic diversity didn’t happen by chance. It’s the result of geography, migration, and cultural isolation over thousands of years. Each valley and tribe tells a story written in its own language — a living record of history and survival.

Mountains, Islands, and Geography Isolation

Papua New Guinea’s landscape is one of the most rugged and fragmented on Earth. Towering mountains, dense rainforests, and countless islands make travel and communication extremely difficult.

- Mountain ranges cut off villages from one another.

- Thick jungles limit movement and contact.

- Many communities are separated by rivers or ocean channels.

As a result, people lived in isolation for generations. Each community developed its regional dialect variations, shaping words and meanings to fit its world. Over time, this natural separation led to the creation of hundreds of unique Papuan languages and dialects across the country — a true reflection of Papua New Guinea’s multilingualism.

Historical Migration Patterns

The story of Papua New Guinea’s languages also begins with ancient migration. Thousands of years ago, waves of settlers from different regions — mainly from Southeast Asia and the Pacific — arrived and spread across the islands.

Over time, these groups became isolated and developed independently, both culturally and linguistically.

More than 800 tribes emerged, each valuing its unique traditions, customs, and speech. In many communities, language became a symbol of indigenous identity, reinforcing the boundaries between tribes.

Limited Mobility and Oral Traditions

For a long time in history, Papua New Guinea’s people lived in small, self-sufficient communities with little movement between regions. Limited mobility kept these communities apart.

- Mountain paths and forests restricted travel and trade.

- The absence of a shared written language allowed each dialect to evolve freely.

Without written records, communication and cultural knowledge were passed down orally through songs, stories, and rituals. This oral tradition helped each language grow independently, rich in metaphor and meaning.

Some evolved through interaction between neighboring tribes, especially in trade or marriage, while others remained completely untouched.

Later, during the colonial era, Tok Pisin (Pidgin English) emerged as a bridge language — a blend of English and local speech used for communication between groups.

Yet despite this shared medium, most indigenous languages of PNG have retained their original structures and vocabularies, preserving one of the richest linguistic landscapes on Earth.

Two Major Language Families and Regional Distribution

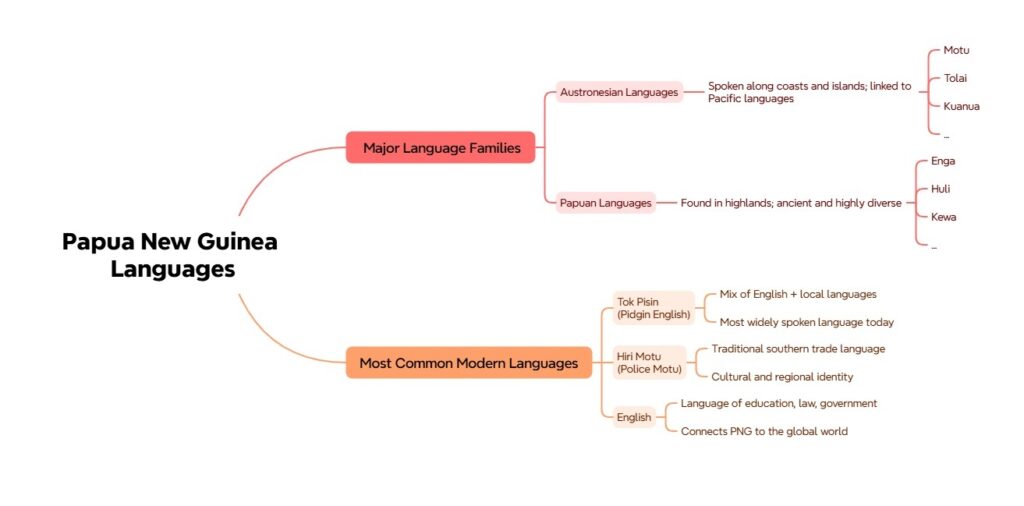

Despite its incredible variety, almost all of Papua New Guinea’s 800+ languages belong to two prominent families — the Austronesian and the Papuan languages.

Their distribution follows geographic patterns: Austronesian languages dominate the coastal and island regions, while Papuan languages are found mainly in the highlands and interior regions. This apparent divide mirrors the country’s topography and its history of settlement and isolation.

1. Austronesian Languages – Voices of the Coast

The Austronesian languages in PNG are mainly spoken along the coastlines and in the islands of Papua New Guinea. They trace their roots to ancient seafaring peoples who arrived from Southeast Asia and spread across the Pacific thousands of years ago.

- Found primarily in coastal villages and island communities where people rely on fishing, trade, and seafaring for daily life.

- Closely related to the languages spoken in Indonesia, the Philippines, and Polynesia, showing clear signs of shared ancestry.

- Examples such as Motu, Tolai, and Kuanua continue to thrive as practical languages for commerce and cultural exchange in coastal regions.

Austronesian languages tend to have simpler grammar and are often used in trade and inter-island communication. Because coastal areas had more contact with foreign traders and missionaries, these languages also absorbed loanwords from English and Malay, making them more adaptable over time.

2. Papuan Languages and Dialects – The Mountain Voices

In contrast, the Papuan languages dominate the country’s interior highlands and remote regions. They are not part of a single unified family, but rather a broad label for hundreds of distinct language groups unrelated to Austronesian languages.

- Represent the oldest languages of the island, spoken long before Austronesian settlers arrived.

- Known for their complex grammar, tonal variations, and intricate systems of classification that reflect the environment and culture of each community.

- Examples include Enga, Huli, Melpa, and Kewa, which are still central to community life and oral storytelling traditions.

Papuan languages are deeply tied to tribal identity. Each one reflects the worldview, myths, and environment of the people who speak it. Many have been preserved through oral tradition, making them not only tools of communication but also living archives of cultural history.

Together, these two language families form the foundation of Papua New Guinea’s linguistic landscape — a vibrant mix of ancient voices and seafaring tongues that continues to shape the nation’s identity today.

Official Modern Language: Tok Pisin, Hiri Motu, and English

In modern Papua New Guinea, three languages stand at the center of national life — Tok Pisin, Hiri Motu, and English. Each serves a different purpose, reflecting the country’s balance between tradition and progress.

Tok Pisin connects people in daily life, Hiri Motu preserves regional heritage, and English links the nation to the world. Together, they shape how Papua New Guineans communicate, learn, and express identity in the 21st century.

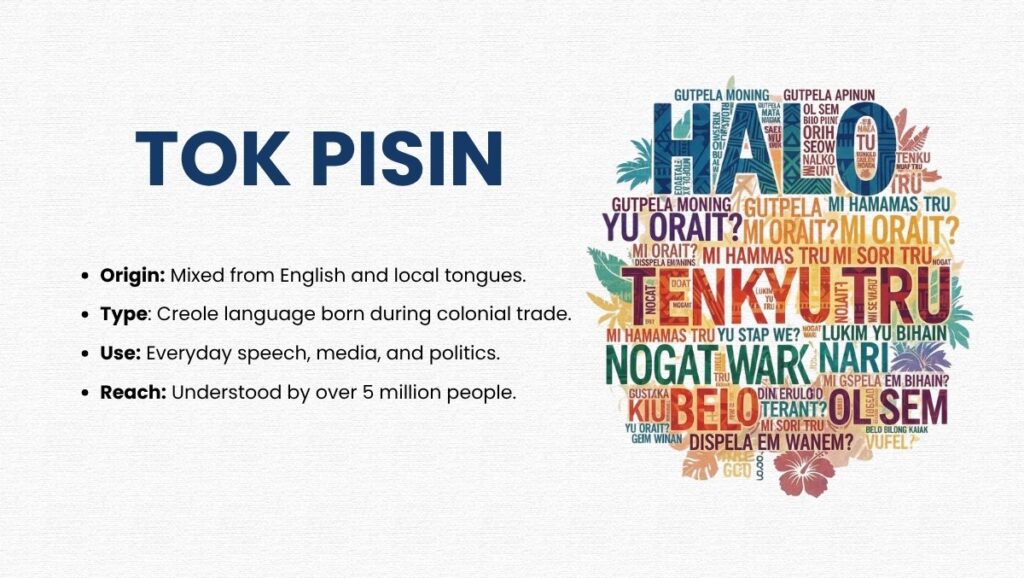

Tok Pisin – The Voice of Everyday Life

Tok Pisin is the heart of Papua New Guinea’s communication. Born during the colonial era as a blend of English and local expressions, it evolved into a creole language widely used daily. You can hear it in markets, on the radio, in schools, and even in Parliament. It’s the true language of the people.

- Origin: Developed from English during the 19th century as plantation workers needed a shared way to communicate.

- Role in society: Spoken by more than 5 million people as a first or second language; used in daily life, politics, and media.

- Distinct feature: Mixes English vocabulary with simplified grammar and local idioms, creating a uniquely expressive national tongue.

Though rooted in English, Tok Pisin has its own rhythm and cultural flavor. It unites communities across mountains and islands, turning linguistic diversity into shared understanding.

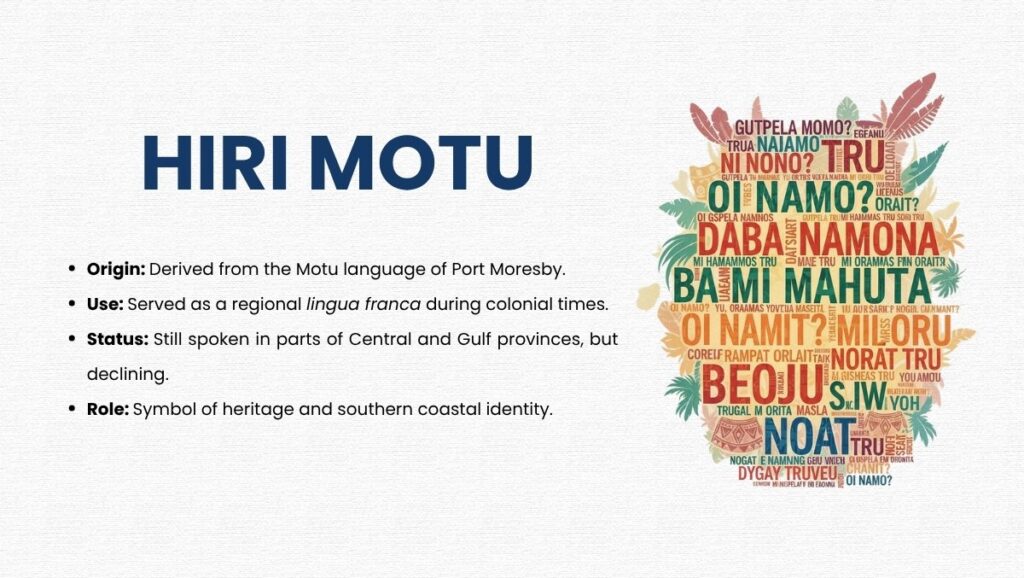

Hiri Motu (Police Motu) – The Language of Heritage and Trade

Hiri Motu reflects the rich trading traditions and culture of Papua New Guinea. It emerged from the ancient maritime trade network known as the Hiri voyages, where coastal Motu speakers exchanged pottery for sago and other goods. Over time, this practical communication evolved into a regional lingua franca.

- Origin: Derived from the Austronesian Motu language spoken around Port Moresby and the Gulf of Papua.

- Historical use: Widely used by colonial police forces and local administration during the British and Australian rule.

- Current status: Still spoken in parts of the Central and Gulf provinces but declining as younger generations adopt Tok Pisin.

Hiri Motu carries deep cultural significance. Although its everyday use is fading, it remains a symbol of southern identity and historical connection among coastal peoples.

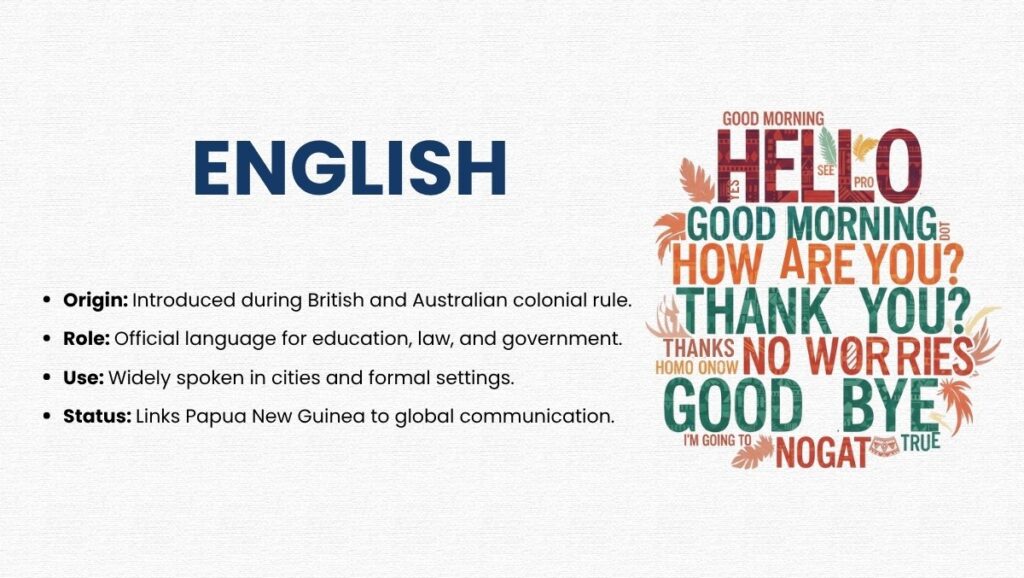

English – The Language of Education and Progress

English represents Papua New Guinea’s link to the modern world. It came with colonization but stayed as the language of education, government, and business. While not everyone speaks it fluently, English remains essential for upward mobility and international communication.

- Origin: Introduced during British and Australian administration and retained after independence in 1975.

- Function: Used in schools, legal systems, media, and official documents; considered a formal and educated language.

- Reach: Primarily spoken by urban residents, government workers, and students; less common in remote villages.

English provides access to global opportunities, but its influence coexists with local identity. Most citizens comfortably switch between English and Tok Pisin, creating a natural linguistic balance between international and local worlds.

While Tok Pisin connects the people, Hiri Motu preserves the past, and English drives progress, these three languages together embody Papua New Guinea’s unique ability to live in multiple worlds at once — traditional, national, and global.

The Future of Papua New Guinea’s Languages

Papua New Guinea’s extraordinary linguistic diversity is now at a crossroads. Urbanization, globalization, and the spread of dominant languages such as English and Tok Pisin are reshaping how younger generations communicate. While these changes bring new opportunities, they also pose a serious threat to the survival of many traditional languages.

In cities like Port Moresby and Lae, more children are now growing up speaking English or Tok Pisin as their first language. This reflects the country’s growing focus on education and global connection, but also leads to the gradual loss of ancestral tongues that once shaped community identity.

The same pattern is seen across Melanesia, where modernization and media continue to erode traditional speech. Yet Papua New Guinea remains a remarkable exception, a linguistic stronghold where hundreds of languages still coexist despite these pressures. Linguists estimate that many of Papua New Guinea’s 800+ languages could disappear within the next century if preservation efforts do not accelerate.

Efforts to protect this linguistic heritage are underway:

- Government-backed initiatives promote bilingual education, encouraging the use of both local languages and English in schools.

- UNESCO supports documentation programs to record endangered tongues and preserve oral traditions.

- Local communities are creating dictionaries, digital archives, and cultural centers to keep their native speech alive.

Safeguarding these languages means more than saving words — it means preserving stories, wisdom, and worldviews that have shaped Melanesian culture for thousands of years. Protecting them means keeping the ancestors’ cultural soul alive for generations to come.

Final Thoughts: The Heartbeat of a Thousand Languages

The story of Papua New Guinea languages is one of extraordinary diversity and resilience. Each language is a living vessel of culture, carrying stories, traditions, and ancient wisdom that define the Melanesian way of life. Together, they weave the identity of a nation where every voice matters.

As modernization spreads, these languages face the risk of fading into silence. Protecting them is not only about preserving communication but also about safeguarding the soul of Papua New Guinea itself. The survival of Papua New Guinea languages is a reminder that linguistic diversity is one of humanity’s greatest treasures — a heartbeat that connects the past, enriches the present, and inspires the future.

FAQs

What language do most people use for daily communication?

Most people in Papua New Guinea use Tok Pisin for everyday communication. It’s spoken widely across regions and understood by the majority of the population.

Is Tok Pisin the same as English?

No. Tok Pisin (Pidgin English) is based on English but has its own grammar, pronunciation, and local words. It’s a separate language, not just simplified English.

How many languages are spoken in Papua New Guinea?

Papua New Guinea is home to around 840 living languages, according to Ethnologue (2024) — the highest number of languages spoken in a single country anywhere in the world.

How to say hello in pidgin English PNG?

In Tok Pisin, you can say “Halo” or “Gutpela Dei”, which means “Good day.” Both are friendly greetings used throughout Papua New Guinea.

I am a cultural historian and editor with over 10 years of research into pre-contact Polynesian history, the Lapita migration, and oral traditions. Share the excitement of my latest publications.

My contact:

Email: [email protected]

Tel: +64 21 456 7890