Easter Island (Rapa Nui) Travel Guide: History, Culture & Top Sights

Remote, enigmatic, and steeped in legend, Easter Island (Rapa Nui) captivates travelers with its ancient moai statues, volcanic landscapes, and living Polynesian culture.

This complete Easter Island travel guide explores everything you need to know — from the island’s fascinating history and art to local traditions, must-see sites, and practical tips for visiting responsibly.

Where Is Easter Island?

Rising out of the vast South Pacific like a lonely emerald, Easter Island, known to its inhabitants as Rapa Nui, is one of the world’s most remote inhabited islands.

It sits about 3,500 kilometers west of Chile, the country that now governs it, and more than 2,000 kilometers east of Tahiti. Though isolated, it forms part of the great Polynesian Triangle, linked culturally to Hawaii in the north and New Zealand in the southwest.

The island covers only 163 square kilometers, yet its volcanic cliffs, sweeping grasslands, and coastal lava plains hold centuries of stories.

With a population of roughly 8,000 people, it’s small enough that travelers can drive from one end to the other in under an hour, but each curve of road reveals a new mystery waiting in the wind.

A Brief History of Easter Island (Rapa Nui)

1. The First Settlers: Polynesian Voyagers Arrive (c. 800–1200 CE)

Archaeological and linguistic evidence suggests that the first Rapa Nui people arrived between 800 and 1200 CE, voyaging from other Polynesian islands by double-hulled canoe.

They brought with them key crops such as sweet potatoes and taro and a deeply spiritual worldview that saw the land, the ocean, and the ancestors as one living network.

According to History.com, archaeological studies indicate that the first Polynesian settlers reached Rapa Nui around 800–1200 CE, establishing one of the most isolated human civilizations on Earth.

2. Building a Unique Culture and Society

Over the centuries, the Rapa Nui Islands developed their own language, art, and leadership structure. Powerful clans ruled the island, and community life centered on Ahu – stone ceremonial platforms that would later support the island’s most iconic creations: the moai statues.

These structures symbolized ancestral reverence and the spiritual connection between people and nature.

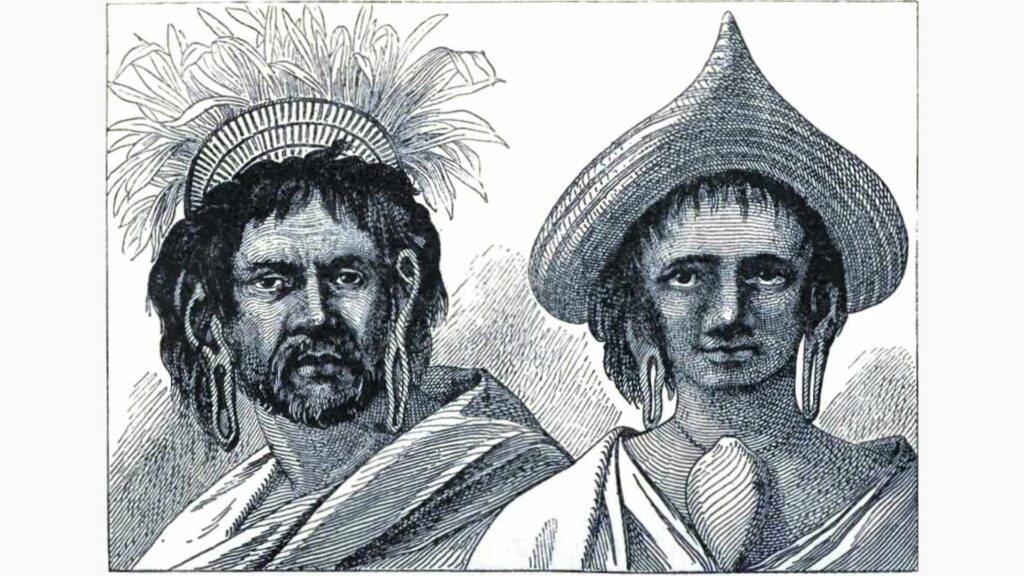

3. European Contact and Cultural Upheaval (18th–19th Century)

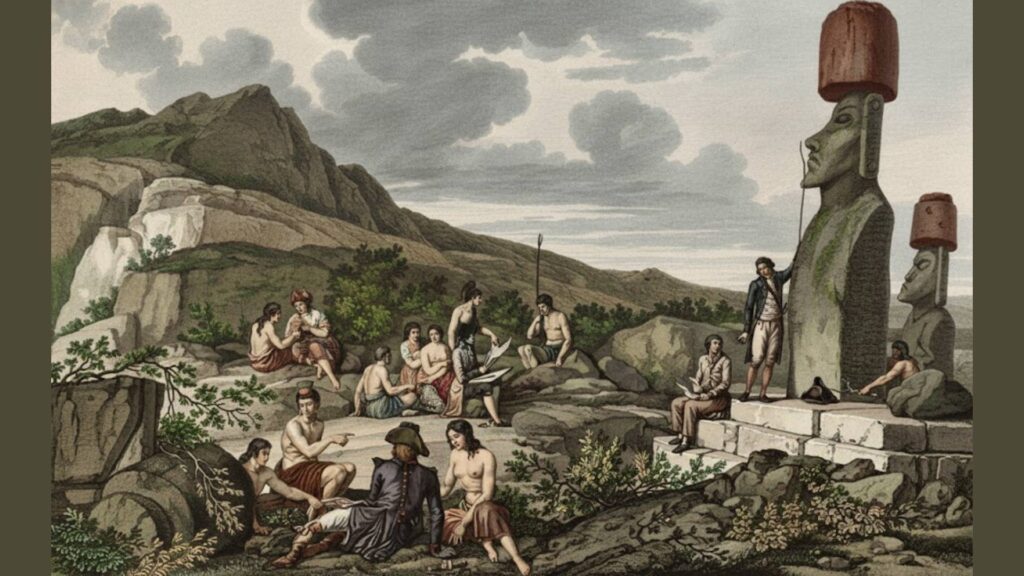

The first recorded European contact occurred on April 5, 1722, when Dutch explorer Jacob Roggeveen landed on the island. Later came Spanish, French, and British ships, followed by Chilean annexation in 1888.

The contact brought devastating consequences such as disease, slave raids, and loss of land. But the Rapa Nui people endured through resilience and adaptation.

4. Survival and Cultural Revival in the Modern Era

In 1888, Easter Island history was annexed to Chile under a treaty signed between Chief Atamu Tekena and naval officer Policarpo Toro. This is a pact Chile viewed as complete annexation, though local tradition saw it as one of friendship and protection.

During the 20th century, Rapa Nui people faced cultural repression, loss of ancestral lands, and confinement to Hanga Roa, while much of the island was leased to foreign ranching companies.

Yet through unity and peaceful protest, they organized councils and movements to reclaim their rights, revive the Rapanui language, and restore local governance.

Today, their resilience lives on through education, environmental stewardship, and the Ma’u Henua Indigenous Community, which manages Rapa Nui National Park and ensures that tourism supports cultural preservation.

The Rapa Nui Culture & People

Despite centuries of outside influence, the Rapa Nui people have preserved a remarkable amount of their heritage. Their Polynesian roots remain visible in language, song, dance, and carving traditions.

Language and Arts

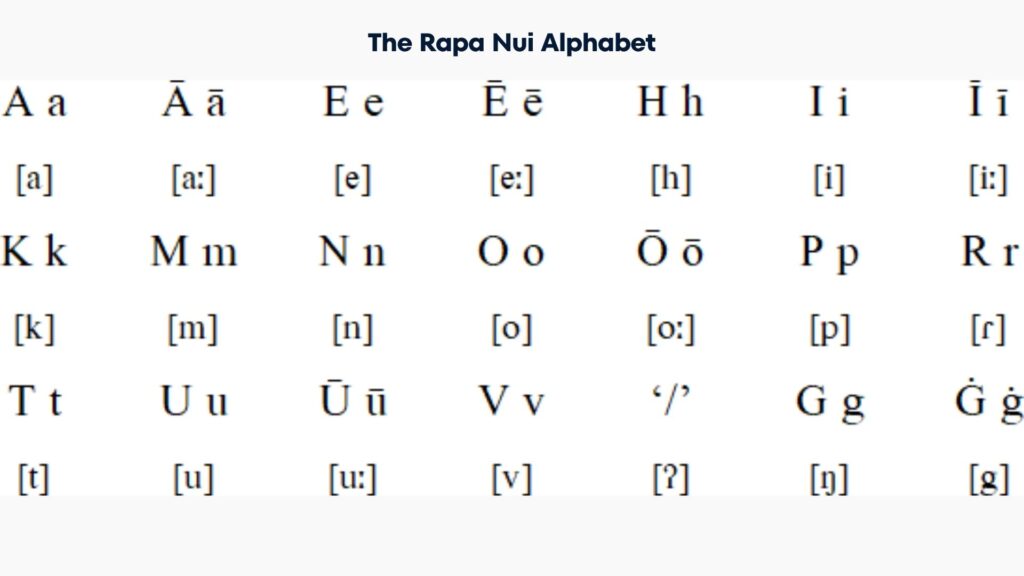

The local tongue, Rapanui, shares similarities with Tahitian and Maori yet carries its own rhythm and vocabulary. Although bilingualism in Spanish is now common, community schools and cultural centers actively teach Rapanui to younger generations to reclaim linguistic identity.

Traditional chants and songs, the dance style Sau Sau, and intricate wood carvings reflect ancestral, mythological, and natural themes from Rapa Nui’s past.

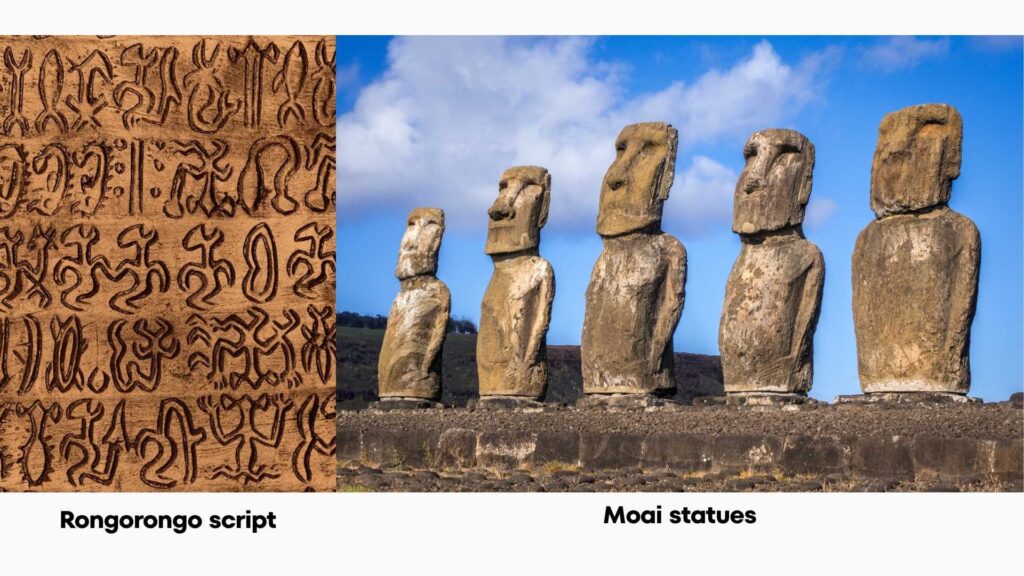

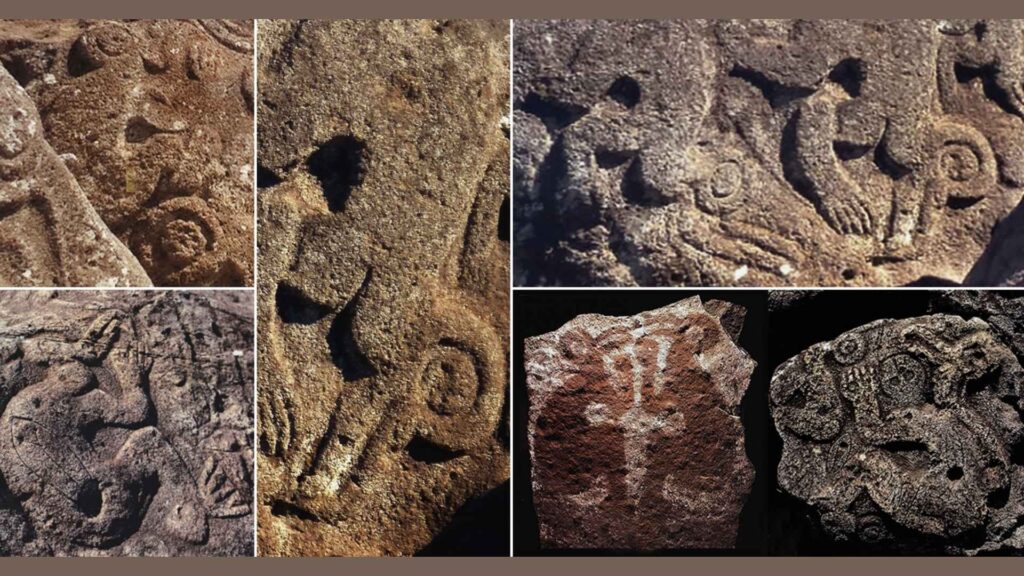

Next, Rongorongo is a mysterious system of glyphs carved on wooden tablets, believed to be a unique form of early writing or symbolic record-keeping.

The script was discovered in the 19th century, featuring human, animal, and geometric figures arranged in alternating lines called reverse boustrophedon.

Though only about two dozen tablets survive today, Rongorongo remains undeciphered, standing as powerful proof of the Rapa Nui people’s creativity and intellectual depth.

Moai: The Iconic Stone Guardians of Rapa Nui

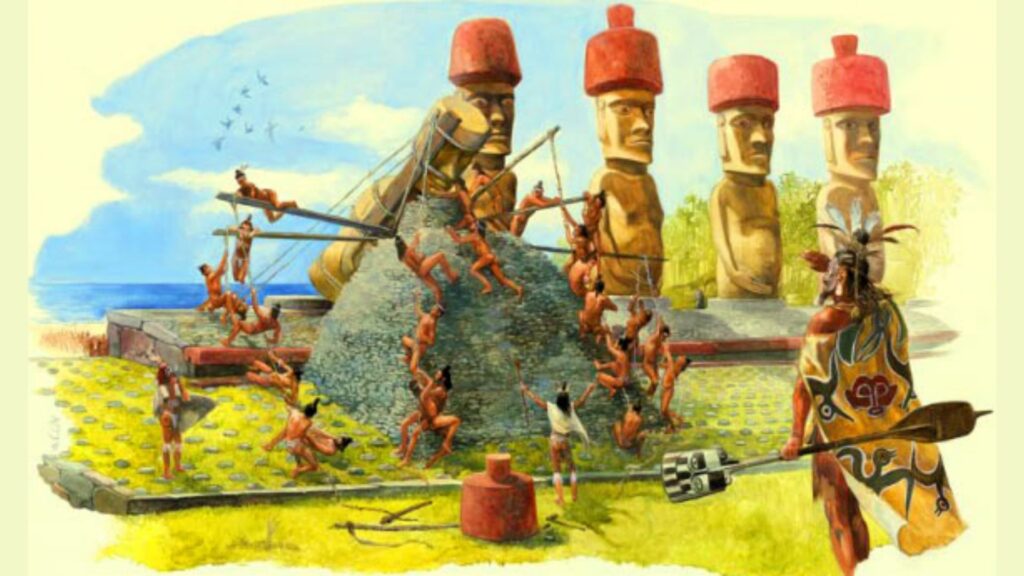

The moai statues are the most iconic symbols of Rapa Nui—over 900 monumental figures carved between 1250 and 1500 CE from volcanic rock at Rano Raraku.

Far from being gods, Moai statues meaning deified ancestors who embody mana, the spiritual power believed to protect the island’s communities.

Each moai was placed on an ahu (ceremonial platform), facing inland to watch over the villages, a lasting expression of artistry, devotion, and ancestral reverence.

Beliefs and Values

At the heart of Rapa Nui belief lies mana: a spiritual force inherited from ancestors that influences respect, leadership, and community balance.

Daily life once revolved around honoring ancestors, maintaining harmony with nature, and observing tapu: an ancient Polynesian tradition passed down through generations.

Tapu represents a sacred order of respect and restraint, a form of discipline meant to protect life, community, and ancestral wisdom. It is this very concept that later gave rise to the English word ‘taboo’.

In later centuries, the Birdman cult (Tangata Manu) emerged, combining spiritual ritual and physical endurance to determine leadership each year.

These traditions continue to shape moral values and collective memory, even as Christianity and modern influences blend into island life.

Social Structure and Family Life of the Rapa Nui people

Rapa Nui society traditionally revolved around extended families and clans (mata), each led by a chief who managed communal lands and represented ancestral authority.

Family ties remain strong today—relatives often share labor in farming, fishing, and ceremonies.

Women historically played key roles in preserving oral traditions and passing down legends. Modern community life maintains this cooperative spirit, balancing individual livelihoods with collective responsibility.

Rapa Nui Cuisine

Traditional Rapa Nui cuisine reflects both isolation and Polynesian heritage. Staples such as sweet potatoes (kumara), taro, yams, and bananas were complemented by abundant seafood, especially tuna, lobster, and swordfish.

Cooking was often done in earth ovens called umu pae, where hot stones slowly baked wrapped foods. Some traditional foods, such as po’e and the communal umu pae oven, remain essential symbols of Rapa Nui heritage, connecting food, family, and spirituality.

Rapa Nui Traditional Clothing

Everyday Wear: The Rapanui people traditionally wore takona (body paint) and a hami, a simple loincloth tied with fiber or hair. Both men and women wore it, though some women also wore a short skirt over it.

Cloaks – Nua Mahute: For warmth or ceremony, both genders used the nua mahute, a short shoulder cloak made from the rare mahute plant fiber. Because the fiber was hard to produce, it was mainly worn by chiefs and high-ranking women.

Headdresses and Hair: Traditionally, hair was worn long and tied up in a pukao (topknot). After European contact, feathered haʻu headdresses made from mahute cloth became popular.

Ornaments and Jewelry: Body adornment symbolized status.

- Ivi Mango: Shark-bone tools used to pierce and stretch earlobes, later decorated with wood, shell, or bone.

- Rei: Necklaces made from plant fiber or human hair, often with pendants of bone, stone, or pearl shaped like fishhooks (mangai).

- Reimiro: Crescent-shaped pendant with carved faces, worn by high-status individuals.

- Tahonga: Coconut-shaped carving, sometimes featuring a bird or human head, symbolizing rank and spiritual power.

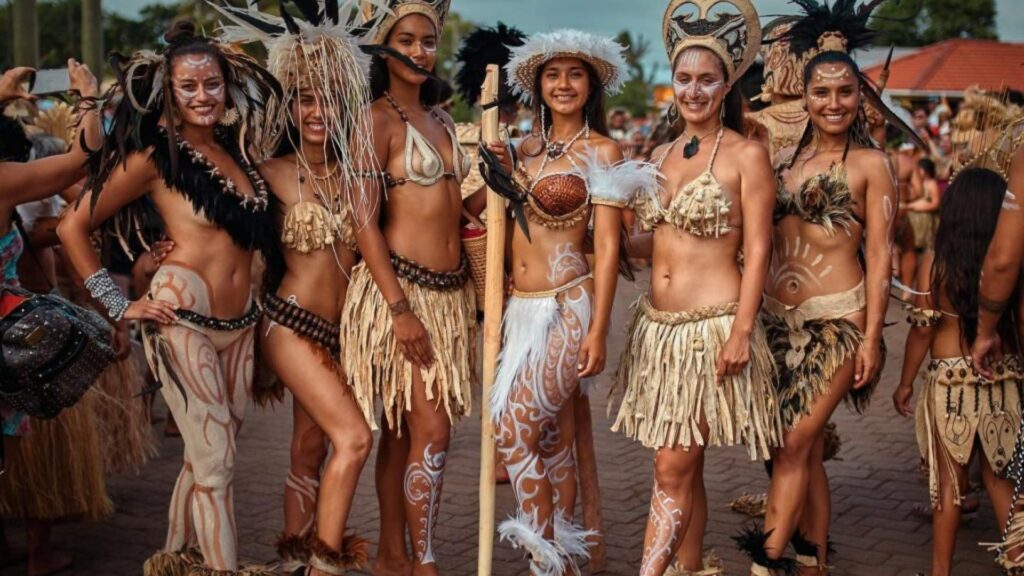

Festivals and Cultural Expression

The most significant celebration, Tapati Rapa Nui, takes place each February. For two weeks, locals compete in canoe races, body-painting contests, and athletic challenges that honor ancestral strength and unity.

Music, dance, and tattoos all carry symbolic meaning—expressing pride, beauty, and spiritual connection. Visitors are invited to participate respectfully, witnessing a vibrant declaration that Rapa Nui culture is very much alive and evolving.

Rapa Nui Today

Today’s Rapa Nui Easter Island blends heritage and modern living. The main town, Hanga Roa, houses most residents along with guesthouses, cafés, and dive shops.

Tourism is the backbone of the economy, but the community carefully balances growth with preservation. Many sites are owned by the local Ma’u Henua community organization, ensuring that entrance fees fund conservation and cultural education.

Modern Rapa Nui society reflects both Chilean and Polynesian influences: Spanish is the language of government, but Polynesian hospitality – warm, proud, and welcoming – shapes social life.

For travelers, understanding the Rapa Nui people means seeing beyond the moai. It’s found in the laughter of children racing on the beach, the rhythm of drums echoing through Tapati nights, and the quiet pride of locals who continue to guard their ancestors’ legacy.

How to Visit Easter Island?

Though remote, visiting Rapa Nui is more accessible than many imagine. Most travelers arrive by plane from Santiago, Chile, a flight of about 5.5 hours. A smaller route from Tahiti connects Rapa Nui with the broader Polynesian world.

If you’re planning your trip, here are some essential Easter Island travel tips to help make the most of your journey.

When to Go

The island enjoys a mild subtropical climate year-round.

- December – March: warm and lively, perfect for beach visits and the Tapati Rapa Nui Festival.

- April – October: cooler, quieter months are ideal for hikers and photographers.

Entry & Park Permits

Much of Rapa Nui is protected as Rapa Nui National Park, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Visitors must purchase a park ticket before exploring archaeological zones such as Rano Raraku, Ahu Tongariki, or Orongo.

Responsible Travel

Local guides encourage guests to tread lightly—stay on marked paths, avoid touching the moai, and support community-run lodges and restaurants.

Respecting land and people isn’t just courtesy; it’s part of the living philosophy of mana and tapu that shapes everyday Rapa Nui culture.

Top Things to Do in Easter Island

1️⃣ Ahu Tongariki

The island’s most dramatic sight—fifteen moai lined shoulder to shoulder against the rising sun. Each statue faces inland, guarding the ancestral village that once thrived here.

2️⃣ Rano Raraku Quarry

Walk among half-finished giants still embedded in the volcanic rock. This is the birthplace of nearly every moai on the island and one of the most atmospheric spots in all Hawaiian — sorry — Polynesian archaeology.

3️⃣ Orongo Ceremonial Village

Perched on the rim of Rano Kau Volcano, Orongo overlooks cliffs that plunge into the sea. It was here that competitors in the birdman ritual risked their lives each year to bring back the first manu tara egg, symbolizing new leadership and renewal.

4️⃣ Anakena Beach

A curve of white coral sand framed by palms—legend says the island’s first settlers landed here. Today, travelers relax beneath the gaze of restored moai while locals gather for picnics and celebrations.

5️⃣ Museo Antropológico Sebastián Englert

Located in Hanga Roa, this small museum provides essential background on Rapa Nui history, language, and everyday life, helping visitors appreciate sites beyond their mystery.

Preserving the Legacy of Rapa Nui

Conservation here is more than protecting statues—it’s safeguarding a living culture. Local organizations such as Ma’u Henua manage heritage sites and reinvest tourism income into education, reforestation, and cultural projects.

Community leaders emphasize sustainable tourism: limiting visitor impact, supporting traditional agriculture, and teaching younger generations to carve, dance, and speak Rapanui. Their efforts ensure that the story of (Rapa Nui) continues to be told by its own people.

Visitors who travel mindfully—choosing local guides, learning greetings like Iorana! (“hello”), and honoring sacred spaces—help strengthen that legacy.

Final Thoughts: The Spirit of Rapa Nui

Beyond its windswept cliffs and stone guardians, Easter Island is a lesson in endurance and connection. The Rapa Nui people have turned isolation into identity, crafting a culture that bridges past and future.

For travelers, to stand before a moai at sunrise is to feel centuries of devotion in the stillness. Yet the real beauty lies in the people who keep that spirit alive—the dancers, fishermen, storytellers, and children laughing in the surf.

Easter Island (Rapa Nui) isn’t just a destination; it’s a living heritage. To know its story is to understand what the world gains when culture, community, and respect endure together across the sea.

FAQs

1. Where is Easter Island located?

It is located in the southeastern Pacific Ocean, about 3,500 km west of Chile, and is part of the Polynesian cultural region.

2. Who are the Rapa Nui people?

The island’s Indigenous Polynesian inhabitants are known for their artistry, navigation, and stewardship of the moai monuments.

3. Why were the moai statues built?

They honor important ancestors believed to protect villages with spiritual power (mana).

4. How can travelers visit respectfully?

Follow park rules, avoid touching the moai, support community businesses, and learn about Rapa Nui culture before you arrive.

5. Is Easter Island safe to visit?

Yes—crime is low, and locals are welcoming. The main challenges are limited flights and the need to book accommodations early.

6. How long should I stay in Rapa Nui?

Most travelers spend 4 to 5 days on Easter Island to see all the main sites without rushing.

I am a cultural historian and editor with over 10 years of research into pre-contact Polynesian history, the Lapita migration, and oral traditions. Share the excitement of my latest publications.

My contact:

Email: [email protected]

Tel: +64 21 456 7890