Makahiki: Hawaiian Festival of Lono & Harvest Season

When the constellation Makaliʻi rises in the Hawaiian sky, it signals the arrival of Makahiki. This ancient festival, deeply rooted in traditional Hawaiian Makahiki practices, honored the Hawaiian god Lono, the deity of agriculture, peace, and prosperity.

Throughout the Makahiki season, villages lit up with ceremonies, games, and decorations. From symbolic processions to colorful Hawaiian Makahiki decorations, the festival was a vivid expression of Hawaiian cultural traditions. Handcrafted kapa cloth, fragrant leis, and ritual offerings turned the celebration into both a spiritual journey and a cultural showcase that continues to inspire Hawaiians today.

The Origins and Spiritual Roots of Makahiki

Have you ever wondered why the Makahiki and Hawaiian New Year look so different from the Western calendar we know today? Let’s explore its name, its role in marking a new year, and its spiritual foundation in the worship of Lono.

The Name and Origins of Makahiki

The word Makahiki carries layers of meaning that reveal its deep cultural roots:

- It is linked to the rise of the Makaliʻi constellation (the Pleiades), a celestial marker in the Hawaiian lunar calendar.

- Some scholars connect it to ma Kahiki, a reference to Kahiki (often associated with Tahiti), reflecting broader Polynesian ties.

- Others view it simply as the Hawaiian word for “year,” showing how the festival symbolized a complete seasonal cycle.

These origins remind us that traditional Hawaiian Makahiki was both a spiritual celebration and a practical way of tracking time and agriculture.

Why Makahiki Was the Hawaiian New Year?

Unlike Western traditions that celebrate New Year’s Day on January 1st, Hawaiians aligned their year with natural and celestial cycles. When the Makaliʻi appeared and the rains of the Hoʻoilo (wet season) arrived, it signaled renewal. Crops were nourished, the land was restored, and communities embraced rest and peace. That is why the Makahiki season was celebrated as the true beginning of a new year in Ancient Hawaiian traditions.

The Role of Lono: God of Peace and Prosperity

At the heart of Traditional Hawaiian Makahiki stood the Hawaiian god Lono. Associated with rain, fertility, agriculture, and abundance, Lono embodied everything the people needed for survival and growth. Under his blessing, warfare was suspended by kapu, ensuring peace. Through offerings of food, fish, and kapa cloth, Hawaiians expressed gratitude and renewed their bond with the land and the divine.

Timeframe and Main Rituals of the Festival

So when exactly did Hawaiians celebrate Makahiki, and what did the festival look like in daily life? The answer is both practical and spiritual — rooted in the stars, the seasons, and the traditions that kept communities connected.

The Moment Makahiki Occurred

The festival did not follow a Western calendar but was guided by the sky and seasons.

- Timeframe: October to March (around four lunar months).

- Celestial sign: The evening rising of Makaliʻi (Pleiades) marked the start.

- Seasonal context: Coincided with the Hoʻoilo season, when rain nurtured crops and the land was renewed.

For Hawaiians, these signs were not just astronomy; they were sacred signals that the year was turning, the land was resting, and the people were entering a time of renewal during the makahiki festival in Hawaii.

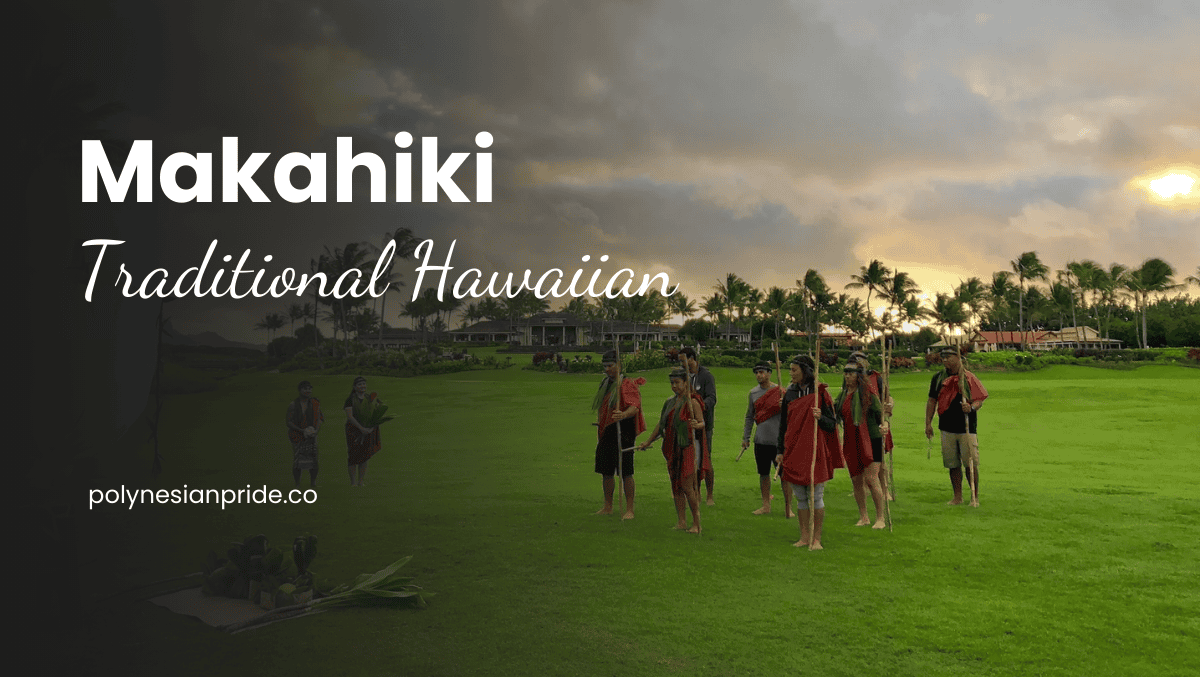

Ceremonies, Offerings, and Processions

Rituals of gratitude were at the heart of Traditional Hawaiian Makahiki. These ceremonies honored the Hawaiian god Lono, ensured harmony between people and land, and strengthened the bond within communities. Two of the most important practices were the presentation of Hoʻokupu (sacred offerings) and the grand procession of the akua loa, a symbolic representation of Lono himself.

Hoʻokupu (Sacred Offerings)

Offerings expressed the community’s gratitude for abundance and their hope for continued prosperity. Chiefs, commoners, and entire families contributed what they could, symbolizing both devotion and unity.

- Agricultural produce: taro, sweet potatoes, breadfruit, and coconuts represented the bounty of the land.

- Seafood and protein: fish and other catches highlighted the importance of the ocean.

- Handcrafted goods: mats, tools, and clothing showed skill and dedication.

- Kapa cloth: a prized contribution, valued for its artistry and symbolic purity.

Through these offerings, Hawaiians acknowledged Lono’s blessings and renewed their covenant with the gods and nature, preserving Makahiki cultural heritage.

The Akua Loa Procession

The akua loa was a tall wooden staff wrapped in white kapa cloth and adorned with feathers, carried through villages as the embodiment of Lono. Its journey transformed Makahiki into a moving festival that reached every household.

- Sacred presence of Lono: the staff embodied divine blessings, bringing peace, fertility, and prosperity wherever it traveled.

- Island-wide connection: by moving through districts, the akua loa ensured that the entire community—chiefs and commoners alike—shared in the festival’s spiritual power.

This traveling ritual connected people across the islands, reminding them that Traditional Hawaiian Makahiki was not only local but a collective celebration of faith, culture, and renewal.

Games and Community Life

Beyond rituals, Traditional Hawaiian Makahiki was a season of joy and renewal — filled with games, music, and sacred rules that paused conflict and strengthened community bonds.

- Makahiki games and competitions: contests such as foot races (heihei), wrestling (hakoko), and spear throwing (ʻōʻō ihe) tested athletic skill, while games of strategy like konane (a Hawaiian board game) challenged the mind.

- Music, hula, and storytelling: traditional chants like oli, hula dances performed in honor of Lono, and epic stories (moʻolelo) kept cultural memory alive and connected generations.

- Social kapu (sacred restrictions): warfare and conflict were suspended, chiefs redistributed food and goods, and the land rested, creating a season of harmony and renewal.

The closing of Makahiki ceremonies marks the end of the season of peace. This transition symbolized a return to daily life, while carrying forward the blessings of the Hawaiian god Lono for prosperity in the year ahead.

Cultural Symbols and Hawaiian Makahiki Decorations

Symbols played a vital role in Traditional Hawaiian Makahiki, transforming the festival into both a sacred ritual and a vibrant cultural display. Each element carried a meaning that linked people, gods, and the natural world.

Traditional Cultural Elements

At the heart of Makahiki were symbols and objects that reflected gratitude, abundance, and divine presence:

- Kapa cloth and textiles: used to wrap the akua loa staff and presented as offerings, kapa symbolized purity, artistry, and devotion.

- Feathers and Kāhili: brightly colored feathers represented chiefly authority and divine blessing, adding prestige and beauty to ceremonies.

- Gourds and calabashes: filled with food, seeds, or water, they embodied nourishment and the prosperity provided by the land and sea.

- Leis and plant garlands: woven from ti leaves, flowers, and native plants, they expressed renewal, aloha, and the close bond with nature.

- Chants, hula, and instruments: performances of oli (chants), mele (songs), and hula dances honored the gods and passed cultural memory through art.

Together, these elements created a multisensory experience — visual, auditory, and spiritual — that defined the essence of Traditional Hawaiian.

Hawaiian Makahiki Decorations in Modern Use

Today, many of these traditional elements inspire Hawaiian Makahiki Decorations in contemporary settings. Kapa-inspired textiles appear in table runners or wall hangings; feather motifs are echoed in modern art pieces; gourds and calabashes are used as natural centerpieces; and leis continue to decorate homes and events, especially during harvest-themed or cultural festivals.

Beyond objects and decorations, Makahiki was also expressed through ceremonial clothing, handcrafted tools, and artistic performances. Chiefs and participants wore garments made of kapa cloth, artisans crafted symbolic items for offerings, and artists expressed devotion through chants, dance, and visual design.

Art was not separate from ritual — it was the language through which spirituality, gratitude, and identity were made visible.

Reviving Makahiki in Contemporary Hawaii

For centuries, Makahiki was the heartbeat of Hawaiian cultural life, but Western colonization and the decline of indigenous practices led to its near disappearance. Yet, beginning in the late 20th century, a cultural renaissance sparked a renewed interest in Makahiki and Hawaiian cultural traditions, bringing this ancient festival back into community life.

- Cultural revival movement: Hawaiian educators, cultural practitioners, and activists reintroduced Makahiki as part of a larger effort to reclaim indigenous heritage, language, and traditions.

- Makahiki today: Festivals are now held in schools, universities, and local communities, where students learn Makahiki games and sports, traditional chants, and rituals. Some events are also celebrated in cultural centers and tourism gatherings, sharing the richness of the tradition with visitors.

- Modern relevance: Beyond its rituals, Makahiki embodies values that resonate deeply in the present day—peace instead of conflict, community solidarity, and an ecological ethic that honors the land and sea.

In this way, the revival of ancient Hawaiian traditions is more than cultural preservation; it is a living practice that inspires younger generations to embrace identity, connection, and stewardship of the environment.

Among the many traditions revived with Makahiki, kapa cloth holds a special place. Once crafted from the bark of the wauke (paper mulberry) plant, kapa was used for ceremonial attire, sacred offerings, and even to wrap the akua loa during processions. Today, kapa is celebrated not only as a symbol of Hawaiian cultural traditions but also as an enduring art form. Modern artisans continue to create kapa-inspired textiles, bridging the past and present while keeping this heritage alive.

Bring Hawaiian heritage home – Discover the Kapa Collection, where ancient artistry meets modern style.

Final Reflections

Makahiki is not only the Hawaiian New Year — it is a symbol of balance, peace, and prosperity. By pausing warfare, redistributing resources, and honoring the land, the festival reminds us of the deep wisdom embedded in Hawaiian harvest festival traditions. These values remain just as relevant in today’s fast-paced world.

What makes Makahiki powerful is the way it bridges the past and the present. Ancient rituals, chants, and Hawaiian clothes traditional for ceremonies now coexist with modern community events and cultural education programs. This blend of tradition and innovation ensures that the festival continues to feel alive, accessible, and meaningful for all generations.

This festival also carries an important role beyond Hawaii’s shores. Through festivals, cultural exchanges, and tourism events, it introduces global audiences to Hawaiian identity, spirituality, and art. For travelers or culture enthusiasts, attending a Makahiki celebration offers more than entertainment — it provides a genuine experience of Hawaiian heritage and values.

If you seek to connect with indigenous traditions, Makahiki is an invitation: to witness rituals, learn through games, admire crafts, and feel the aloha spirit that has guided Hawaiians for centuries. It is a celebration of life, community, and the enduring harmony between people and nature.

FAQs

What games and ceremonies were part of Makahiki?

Makahiki featured athletic contests like foot races, wrestling, and spear throwing, along with board games such as konane. Ceremonies included offerings (Hoʻokupu), chants, hula, and the procession of the akua loa in honor of the god Lono.

Why was warfare forbidden during Makahiki?

Warfare was suspended to honor peace under the protection of Lono. This pause allowed communities to rest, redistribute resources, and focus on renewal instead of conflict.

Are drinks included at Makahiki?

Yes. Offerings often included ʻawa (kava), a ceremonial drink, along with water and other natural beverages. These drinks symbolized hospitality, spiritual connection, and the abundance of the land.

What is the traditional Hawaiian cloth for Makahiki?

The traditional cloth is kapa cloth, made from the bark of the wauke (paper mulberry) plant. It was used for ceremonial attire, to wrap offerings, and to decorate sacred objects.

I’m a lifestyle curator who has blended Polynesian foodways and fashion into everyday life for over five years. I celebrate makers, materials, and style—with heritage as the headline, not the footnote.

My contact:

Email: [email protected]

Tel: +689 87 246 367