Maori People’s Beliefs: Deep Insights and Rich Traditions

Maori people’s beliefs are deeply rooted in their connection to nature, ancestors, and gods, forming a spiritual and cultural heritage that has guided their way of life for centuries. As the indigenous population of New Zealand, the Māori people’s worldview emphasizes interconnectedness and respect for all life. Understanding Maori people’s beliefs reveals their spiritual practices and offers valuable insight into the cultural values that continue to shape modern Maori society.

I. Core Aspects of Maori People’s Beliefs

Mauri, Mana, and Tapu

Three fundamental concepts form the core of traditional Maori people’s beliefs: mauri, mana, and tapu.

- Mauri: Mauri is a pervasive life force akin to the concept of a soul. It is present in all living things and connects the physical and spiritual worlds. A person’s mauri influences their individuality and well-being, and maintaining balance is crucial for harmony in life.

- Mana: Mana is a spiritual power or essence derived from the atua. It can be inherited through ancestry or earned through skill, bravery, or social recognition. Mana is a crucial determinant of social status; it is highly respected and protected. Losing mana, especially at the hands of others, was historically a common cause of conflict and warfare among tribes.

- Tapu: Tapu is closely linked to mana and refers to a sacred or forbidden quality. It involves rules and prohibitions that govern interactions between people, places, and objects. There are two types of tapu:

Private Tapu: Related to individuals, often reflecting their mana or status.

Public Tapu: Applied to communities or places, such as burial grounds (urupā) and sacred sites.

Violation of tapu could lead to severe consequences, including sickness or death. Traditional Maori society was almost theocratic, as fear of the gods and respect for tapu maintained social order.

Tohunga and Whakapapa

Tohunga were experts or priests who specialized in various disciplines governed by tapu. They played essential roles in healing the sick, advising leaders, foretelling the future, carving canoes, and more. Knowledge was passed down orally from master to apprentice at specialized schools. Both men and women could serve as tohunga, though they performed different roles in line with gender-specific tapu.

Whakapapa, or genealogy, is fundamental to Maori culture and crucial to the Maori people’s beliefs. It connects individuals to their ancestors, the environment, and the gods, often represented through meaningful Maori symbols that embody these spiritual relationships.

Maori believe everything is interconnected through whakapapa, forming an extensive network linking humans with nature and the spiritual realm. This connection is a constant reminder of the Maori’s responsibility to maintain balance and harmony in their relationships with others, the land, and their cultural traditions.

Atua (Gods)

The Maori people’s beliefs and spirituality revolve around a pantheon of gods, or atua, who inhabit the natural world and influence human affairs. Central to Maori cosmology are Ranginui (the Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (the Earth Mother), whose separation by their children created the world and its elements. The atua are responsible for various aspects of life and nature:

- Tangaroa: The personification of the ocean and the ancestor of all fish.

- Tāne: The personification of the forest and the origin of all birds.

- Rongo: The personification of peace and agriculture associated with cultivated plants.

- Tāwhirimātea: The personification of storms and weather.

These gods and their stories are central to Maori mythology and are still significant in modern Maori culture.

Wairua (Spirit)

The concept of wairua (spirit or soul) is another essential element of the Maori people’s beliefs. The wairua exists within each individual and continues beyond death, embarking on a journey to Hawaiki, the ancestral homeland. This belief underscores the Māori understanding of the close connection between the physical and spiritual worlds. Wairua not only shapes Maori views on life and death but also influences their rituals, ceremonies, and social customs.

Interconnectedness with Nature

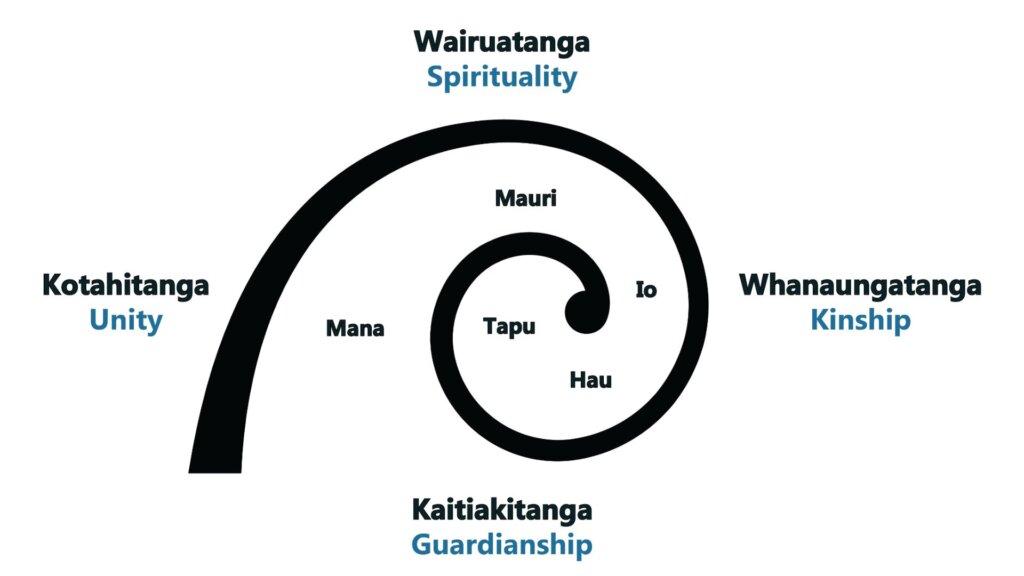

The Maori people’s beliefs view nature as a living entity, with humans being deeply intertwined with their environment. This belief is encapsulated in Kaitiakitanga (guardianship), which emphasizes the moral responsibility to protect and care for the natural world.

Forests, rivers, mountains, and seas are considered ancestors, demanding respect and stewardship. This close bond with the environment is reflected in many of their spiritual practices, ensuring that interaction with nature is always sustainable and respectful.

II. Rituals and Practices in Maori People’s Beliefs

Traditional Maori Rituals: Karanga, Haka, and Whakairo

Traditional Maori rituals such as Karanga (ceremonial call), haka (a war dance or challenge), and whakairo (carving) are important Maori cultural customs with deep spiritual significance in the people’s beliefs.

These practices connect the participants to their ancestors and the atua, providing a way to honor the past and invoke spiritual energy. The karanga is typically performed by women to open ceremonial gatherings. At the same time, the haka is used to inspire or challenge, often in times of war or during important ceremonies.

Marae and Tangihanga

The marae (sacred meeting place) is the heart of Maori community life. It plays a central role in the Maori people’s beliefs. It serves as a gathering spot for important ceremonies, including tangihanga (funeral rites).

The tangihanga is a critical ritual in which the community mourns and celebrates the deceased. The body lies in state at the marae, and visitors pay their respects through speeches, prayers, and songs. The blending of Christian and traditional Maori elements in this ritual highlights the ongoing adaptation of Maori spirituality in the modern world.

Karakia (Prayers)

Karakia are prayers or incantations used to invoke spiritual guidance and protection, a vital part of the Maori people’s beliefs. They are spoken before essential tasks such as embarking on a journey, building a home, or blessing food. Karakia reflects the belief in the pervasive presence of the gods and spiritual forces in everyday life, showing that the Māori seek divine assistance and protection in all aspects of their existence.

The Role of Elders

Kaumātua (elders) hold a revered place in Maori society. As the custodians of knowledge and tradition, they pass down cultural and spiritual practices to the younger generations. Their wisdom and experience are essential in maintaining the spiritual integrity of the community, and they often lead rituals, offering guidance to the people. This is a significant aspect of the Maori people’s beliefs system, where elders serve as living links to their ancestors.

III. Historical and Modern Influences

Maori Migration and Settlement

The migration of the Māori from their Polynesian homeland to Aotearoa (New Zealand) was a significant event that shaped the Maori people’s beliefs. As they settled in the new land, they adapted their spiritual practices to reflect the unique environment, incorporating the land’s natural features into their worship of the atua. Their deep connection with the land became a defining characteristic of Maori spirituality.

Impact of Christianity

The arrival of European settlers in the 19th century brought Christianity to the Maori people, leading to a transformation in their spiritual practices. While many Māori converted, they maintained traditional beliefs like mana (spiritual power) and tapu (sacredness). This resulted in a unique blend where Christian karakia (prayers) became part of Māori gatherings and ceremonies. However, this shift also contributed to the decline of some traditional roles, such as tohunga (spiritual leaders).

Christianity was introduced to the Māori in the early 1800s and initially embraced for its promise of peace and stability, which helped end inter-tribal conflicts. The Church of England, the Roman Catholic Church, and other denominations attracted many converts. Additionally, Māori-led movements like Rātana and Ringatū emerged, integrating Christian teachings with traditional Maori spirituality.

Today, Maori spirituality is diverse, blending traditional beliefs with Christianity. Christian karakia remains central in many gatherings, and rituals like Tangihanga (funeral rites) incorporate Christian and traditional elements, reflecting an enduring cultural synthesis.

Contemporary Expressions

In modern times, Maori people’s beliefs are experiencing a revival. Efforts to preserve traditional practices, language, and rituals are flourishing, and concepts like Kaitiakitanga influence New Zealand’s environmental policies. While many Māori continue to integrate Christian and traditional beliefs, there is growing interest in reconnecting with ancient Māori spirituality, as seen in the resurgence of Maori festivals, art, and ceremonies.

IV. Conclusion

Maori people’s beliefs are a vital part of New Zealand’s cultural heritage, rooted in the principles of mana, tapu, whakapapa, and an enduring connection to nature. Despite the pressures of colonization and the influence of Christianity, Maori spirituality has shown remarkable resilience. Today, these beliefs continue to shape Māori identity and the broader cultural landscape, offering a unique perspective on the interconnectedness of life, nature, and the spiritual world.

FAQs

What are the main beliefs of Māori?

Traditionally, Māori recognised a pantheon of gods and spiritual influences. From the late 1820s, Māori transformed their moral … The Māori natural world teemed with gods and unseen beings and required thoughtful navigation. Tohunga (priests) assisted people with special incantations and rites to appease the gods.

What are the Māori ethical beliefs?

This Māori ethics framework has four tikanga-based principles: • whakapapa (purpose), • tika (research design), • manaakitanga (cultural and social responsibility), and • mana (justice and equity). Each principle is explained in terms of three levels that identify progressive expectations of ethical behaviour.

What are the main values in Maori culture?

Manaakitanga: generosity – honouring, caring and giving mana to people, thus maintaining your own mana. Whanaungatanga: family values, relationships. Wairuatanga: balance – harmony, spirituality, being grounded, calm. Kaitiakitanga: caretaker/guardianship of knowledge, environment, and resources.

What role do elders play in Maori spirituality?

Kaumātua (elders) are the keepers of Maori traditions and spiritual knowledge. They are responsible for leading rituals and passing down cultural practices to younger generations, ensuring the continuity of Maori people’s beliefs.

How has Christianity influenced Maori beliefs?

Christianity was introduced to the Māori by European settlers in the 19th century. While many Māori converted, they blended Christian practices with their traditional beliefs, incorporating mana, tapu, and karakia into their spiritual lives.

I am Leilani Miller – I research focusing on Vanuatu – volcanic landscapes, blue holes, coral reefs & rainforests. I have over five years of experience researching and sharing insights on tourism and environmental activism. Explore and experience without limits through my latest article.

Contact information:

Email: [email protected]

Tel: +1 (808) 555-1528